The Sacrifice of the HMS Jervis Bay

Listen here: https://www.spreaker.com/episode/hwts-009-the-hms-jervis-bay--45392507

Today, we are going to discuss the fate of the British convoy HX-84 after it was intercepted by German surface raiders on November 5, 1940. HX-83 departed Halifax Harbor, Nova Scotia on October 28, 1940, with its ultimate destination being Liverpool, England. This was just one of the hundreds of Allied convoys that fought their way across the Atlantic Ocean between 1939 and 1945. A converted merchant ship, the HMS Jervis Bay, had a rendezvous with destiny while serving as an escort for its fellows.

Given Britain’s reliance on the merchant convoy system during World War I, its reestablishment was a high priority for the Royal Navy and British Government at the outbreak of World War II. The convoy system had been originally developed to combat the German U-boats and surface raiders which attacked British shipping. Their dependence on imported food, fuel, raw materials, and weapons was of key strategic importance if the British had a chance of defeating Nazi Germany. The vast resources and manpower of the Empire still needed to be transferred from the various parts of the Commonwealth to the battlefield. When World War II broke out on September 1, 1939, the Royal Navy immediately implemented convoys to protect their merchant ships.

Having to provide escorting warships for those convoys posed a serious strategic problem during the first two years of the war. During the Interwar Period, roughly 1919-1939, budgetary concerns and international naval treaties prevented the Royal Navy from constructing the necessary light craft to protect the sea lanes. The London and Washington Naval Treaties limited the number of new warships each country could build. Nations needed to decide whether to build new warships or to modernize older ships under the terms of the treaties. In addition, The Great Depression crippled the budgets that were available for the British military, and Royal Navy in particular.

Because of the Royal Navy’s construction budget for new ships was so tight, the numbers of smaller classes of warship like destroyers, frigates, and corvettes did not grow much. The destroyers were especially in short supply because they were used to shield larger warships, like battleships, cruisers, and aircraft carriers, from air and submarine attacks on top of their ability to serve as convoy escorts. Another demand on the limited number of available destroyers was the need to defend Great Britain itself from naval bombardment or amphibious invasion by the Nazis.

Once the storm clouds of war gathered in Europe, the British Government authorized the Royal Navy to increase its building program. It would take time to design and construction the new warships, as well as train their crews. New classes of destroyers, frigates, and corvettes were quickly put into production, but they were months away from being finished when the war broke out in September 1939. Heavier units of the Royal Navy, battleships, and aircraft carriers were also in short supply and could not be shifted to cover convoys without opening danger for the theaters they had been assigned to cover.

The inspiration for a temporary stopgap was found to provide escorts for the newly reestablished convoys: auxiliary merchant cruisers, or AMCs. These were merchant freighters, or even passenger liners, that were requisitioned by their country’s navy and refitted with deck guns. After the conversion, the auxiliary cruisers could act as either escorts, or they could raid the enemies merchant ships. During World War I, these types of ships were used extensively. After trial and error in World War II, it was decided that passenger liners could still be armed but would be better used to transfer soldiers and not act as convoy protection.

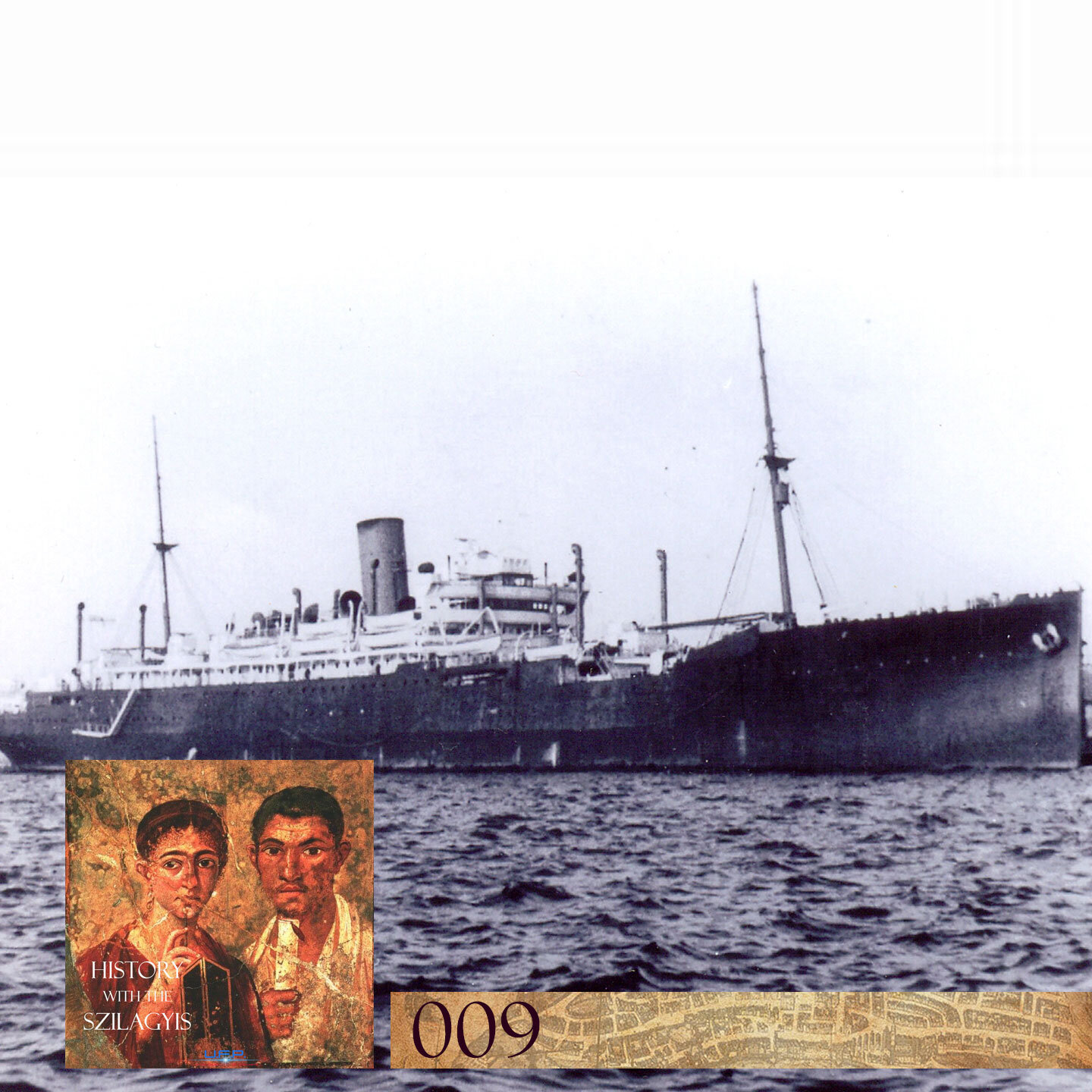

One of the early liner ships to be converted into an auxiliary cruiser was the SS Jervis Bay. The ship was constructed in 1922 to serve as a Commonwealth Line Steamer. Once war broke out, the Jervis Bay was requisitioned by the Royal Navy and underwent a refitting that added seven 6-inch naval guns and two 3-inch anti-aircraft guns. Initially, she was stationed in the South Atlantic but was shifted to Bermuda. By October 1940, Jervis Bay was operating as the sole escort for a small convoy sailing from Bermuda to Nova Scotia. Once there, this smaller convoy would merge with other ships waiting to sail to Liverpool in a larger formation: HX-84. Jervis Bay again was left as the sole escort for a convoy of 37 other merchant ships.

The Royal Navy did not have provide more escorts HX-84 because of operational demands elsewhere. British battleships, cruisers, and destroyers were stationed in Home Waters, the area directly around the British Isles, to prevent German warships from breaking out into the Atlantic or covering an amphibious invasion of England. Other warships were spread throughout the Caribbean Sea, the Mediterranean Sea, the South Atlantic, the Indian Ocean, and the Pacific Ocean protecting British possessions. The Germans had also converted merchant ships into auxiliary cruisers that needed to be hunted down.

Unfortunately for HX-84, a German pocket-battleship, the KMS Admiral Scheer, had sailed past the British Home Fleet and was prowling southwest of Iceland. German pocket-battleships were designed to be raiders that could destroy enemy merchant ships and not have to fight their contemporary enemy warships. They could sail for thousands of miles, were faster than most Allied battleships, and carried heavier firepower than most small escort ships. The Nazis built this type of ship to challenge the Royal Navy’s control of the sea.

On November 5, 1940, the Scheer located HX-84 and prepared to slaughter the convoy. The German commander was completely taken off guard by the aggressive actions of Captain Edward Fegen, commander of the Jervis Bay. Heavily outgunned, outranged, and outclassed in speed, the Jervis Bay sped to intercept the Scheer. Fegen ordered the merchant ships in the convoy to scatter while he bought them time to run. The Jervis Bey fired on the Germans with no hope of surviving the encounter. For 22 minutes, the heavier shells from the Scheer ripped through the liner, injuring, or killing most of the crew. Captain Fegen, and most of his crew, stayed aboard the Jervis Bay until it was sunk.

This engagement took place just before sunset and the Jervis Bay slowed the Germans enough for the convoy to start scattering. After sinking the auxiliary cruiser, the Germans next attacked, and sank three more freighters. As darkness fell, the Scheer continued hunting the British freighters throughout the night. She encountered the SS Beaverford during this pursuit and spent four hours trying to sink her. This was another boon for the surviving ships as they scattered even further. In total, the Scheer destroyed six of the 38 ships in the convoy. The casualties would have been much heavier if not for the actions of Captain Fegen and his crew.

Edward Fegen was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross for his gallantry in engaging the Admiral Scheer. His citation for bravery was published in the November 22, 1940, edition of the London Gazette as follows:

The KING has been graciously pleased to approve the award of the VICTORIA CROSS to the late Commander (acting Captain) Edward Stephen Fogarty Fegen, Royal Navy for valour in challenging hopeless odds and giving his life to save the many ships it was his duty to protect.

On the 5th of November, 1940, in heavy seas, Captain Fegen, in His Majesty's Armed Merchant Cruiser Jervis Bay, was escorting thirty-eight Merchantmen. Sighting a powerful German warship he at once drew clear of the Convoy, made straight for the Enemy, and brought his ship between the Raider and her prey, so that they might scatter and escape. Crippled, in flames, unable to reply, for nearly an hour the Jervis Bay held the German's fire. So she went down, but of the Merchantmen all but four or five were saved.