The First Transition of Power in the United States

—Chrissie

Listen here: https://www.spreaker.com/user/bqn1/hwts143

At the turn of the nineteenth century and just twelve short years since the institution of the American Presidency, the country faced its first contested election. At this time, the electors did not vote separately for President and Vice President; they chose two of the candidates without indicating who should serve in which office: whoever got the most votes was President, the second-most, Vice President.

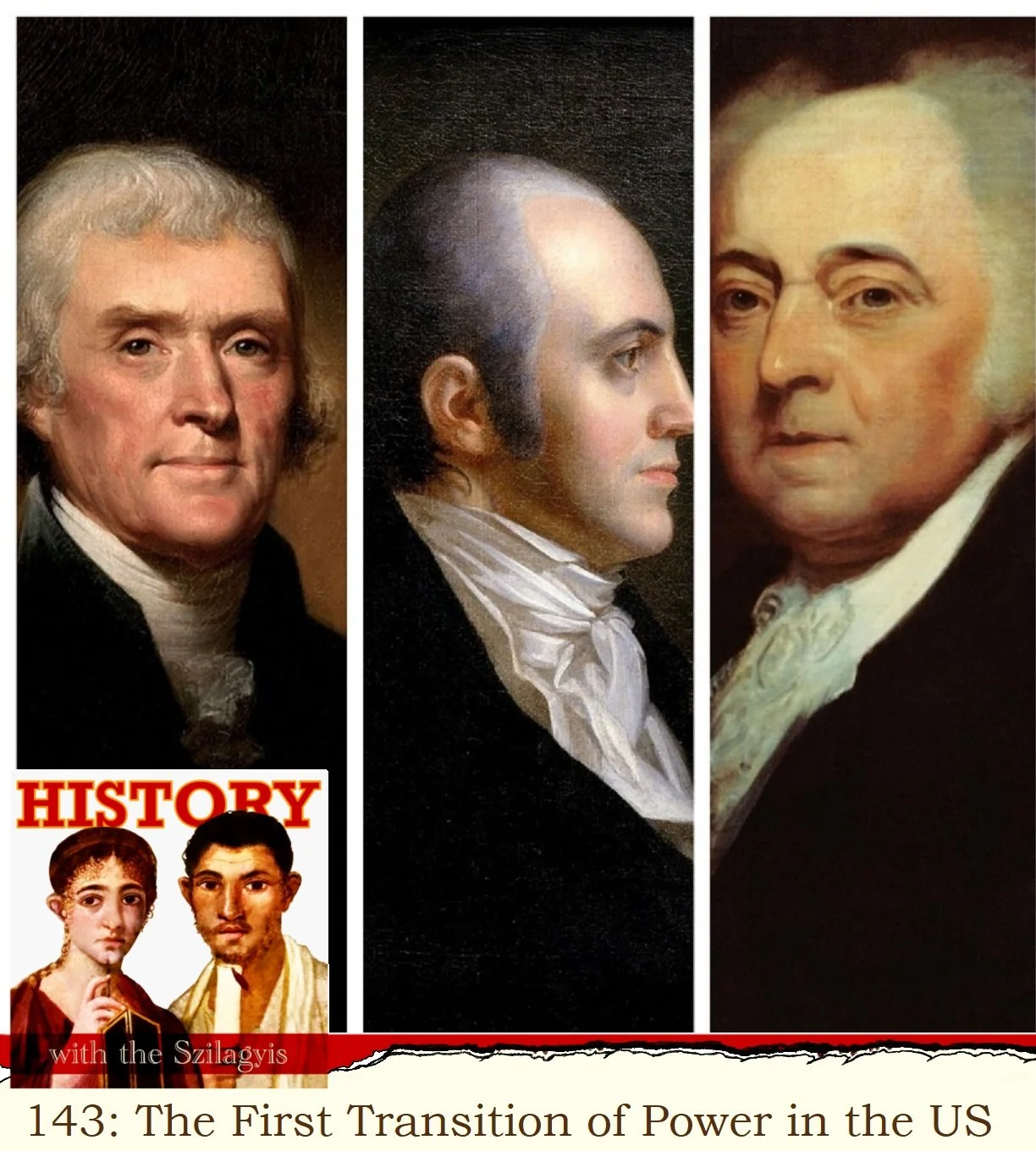

The first two presidential elections had a foregone conclusion in the person of George Washington. John Adams was chosen as his vice president each time. By the second election, they were identified as members of the Federalist party. In 1796, when Washington decided not to run for a third term, the two frontrunners were his vice president, Adams, and Thomas Jefferson, who had served in the Washington administration as Secretary of State and was also de facto head of the opposition party (the Democratic-Republicans). Adams won the presidency and Jefferson the vice presidency, leading to a contentious term in office for both.

In 1800, there were three main candidates, Adams, Jefferson, and Aaron Burr. Adams came last in the electoral vote with the other two men tied. This prompted two unprecedented circumstances: the next president would be of a different party from the previous, and there was a tie that needed to be broken to determine who would be president. The latter was a circumstance for which the Constitution had prepared: a tied presidential election was passed to the House of Representatives, where each state had one vote. In this instance, it took thirty-six rounds of voting over eight days before Jefferson was chosen as the president and Burr the vice president. Both men, and their supporters, accepted the election without question. The former issue, that of the shift from one president to another who had conflicting views was expected to happen, but the framers had not anticipated the partisanship that had so quickly developed. Many had, in fact, written and spoken extensively in opposition to the formation of political parties at all and had hoped never to see them emerge in the United States.

People were anxious that political disagreement would lead to violence. There was little historical context for how the American government operated: it was hoped that the change of power would be as mundane as had been in the Roman Republic, but it was deemed just as likely that a war could break out, as had so often in Europe between rivals for a crown. And, it had not been so long before that a violent revolution had birthed the United States, which, despite its name, was far from united.

Ill-feeling and arguing abounded. The transition period was rife with partisan shenanigans: Adams appointed as many judges as he could before Jefferson’s inauguration in hopes of slowing down or stopping some of his successor’s agenda; when Jefferson came into office, his administration conducted a series of partisan prosecutions to remove Federalists from their appointed positions. But no one disputed the legitimacy of the results and there was no election-driven violence.

The American Experiment appeared to be vindicated: a complete turnover to an administration with the opposing ideology had occurred and the country had survived. A promise to the future existed in this—a promise that no matter how bitterly fought, how much mud was slung by one candidate or party at another, the will of the people (or, at least, their representatives) would and must prevail. Even as secession loomed over the 1860 election, the result of the vote was not questioned. Its inherent legitimacy led those states who disagreed with Abraham Lincoln’s abolitionist ideology to remove themselves from the Union, but they never claimed he had not been properly elected.

This episode of History with the Szilagyis was published on the day of the United States’ Midterm Elections in 2022 (8 November). The presidency is not on the ballot (hence “mid-term”) but the entirety of the House of Representatives and thirty-four of the one hundred seats in the Senate are. The American presidency is not designed to be a dictatorship, the president can do very little without the legislatures’ support and an opposition legislature can be incredibly damaging to any president’s agenda, even as simple obstructionists. While all elections are important, this year’s is presenting itself as a referendum on whether the democratic nature of the United States should continue. This sounds hyperbolic, we are fully aware, but it is not. The Republican Party’s candidates and leadership have made it clear that, should they gain power, the requirements for voting will become much more strict, in favor of fewer people having the franchise. They have also been clear that they will create means by which elections that do not go in their favor can be ignored. This is the first major nationwide election since the failed coup conducted by members of the Republican Party on 6 January 2021. That attempt to circumvent the will of the people was stopped only because those in power trusted that our institutions were legitimate and sought to uphold them. It has been said that a failed coup is merely a rehearsal, a means to see what will and will not be tolerated, so that adjustments can be made to assure success next time. For all that the United States was built by men who espoused great ideals of freedom and self-determination while also holding people enslaved, conducting a genocide on the indigenous peoples, and excluding women from participating fully as citizens, the ideals were and are sound, and must be protected.