The Oxford English Dictionary

—Chrissie

Listen here: https://www.spreaker.com/user/bqn1/hwts159

Dictionaries as we think of them in the modern day, an alphabetical listing of words with their definitions, are a relatively new idea. Translation dictionaries have existed almost as long as the written word. It wasn’t until the seventeenth century that we see efforts toward dictionaries that gave definitions, and most of these were for specific trades or academics. Samuel Johnson gets credit for the first generalized English dictionary, published in two volumes in 1757. It is very much a product of its time and creator, providing definitions that have elements of truth, but are more revealing of the author’s opinion on the topic. It was also, even in two volumes, relatively short: it contained only 40,000 entries.

By the middle of the next century, the Philological Society of London had decided to create a new dictionary. It was to contain not only the words and definitions, but also the history of the word, including its origin and changes in meaning and spelling. It would be as complete an account of the English language as possible, reaching back to the ninth century.

The Philological Society expected it would take a decade to produce what was expected to be a four-volume, 6400-page work. A very slow start began in May 1860 under the direction of Herbert Coleridge. He brought together the work of many volunteer readers, who were providing examples of words as used in quotations which would be used to demonstrate the meaning of the word. He arranged a pigeon-hole grid for the organization of the nearly 100,000 example slips he was sent over the next year. He died in April 1861, just as the first few example pages were ready for publication. He was replaced by Frederick Furnivall, who was a skilled lexicographer and enthusiastic about the project, but his personal interests, particularly with women, eventually overshadowed his qualifications. He was replaced in 1879, having compiled a great many definitions and examples, but having not found any company willing to publish the work. The new director, James Murray, worked out an agreement with Oxford University to publish the work (this is how it ends up with the title “Oxford English Dictionary”). In the twenty years since the project began (twice the original timeline) progress had been slow, but this was blamed on the lack of a publisher; now that Oxford was contracted, the original ten-year timeline was expected to complete the work.

Volunteers were again collected, who sent in 3x5 cards with quotes and citations, all of which were organized in a massive grid. The work went on at a good pace but, after five years they had only reached the word “ant.” It was at this point Murray threw open as large a net as possible—he produced a pamphlet explaining the project and giving instructions on how to participate, to be placed in every English-language bookstore and library across the globe. He was soon receiving a thousand of the 3x5 cards each day at his specially-built office, the Scriptorium. And, as you might imagine, that number grew immensely over the years. More assistants and editors were hired, with each assigned a section of the alphabet.

The most prolific of the volunteer word-finders was Dr. William Chester Minor, whose involvement was conducted entirely from his rooms at the Broadmoor Asylum in Crowthorne, Berkshire, England, where he was incarcerated for murder. Minor was a well-educated American physician who had been mentally broken by his experiences as a surgeon in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He moved to London in 1871 in hopes of improving his mental condition, but to no avail. In a moment overcome with paranoia, he shot and killed a man named George Merritt, who Minor believed had broken into his home. Though he was deemed not guilty by reason of insanity he obviously needed care and supervision and so was set up in relative comfort at Broadmoor. There, he collected a massive library, and the call for examples from Murray and his fellow editors was a way to focus his intellect and, perhaps, a distraction from his continuing mental health struggles. Between 1878 and 1902, Minor sent in hundreds of notecards on a weekly basis. His library had become such a resource for the editors that they sent him lists of words that needed examples, in hopes that he would find them in his collection. It was not until after nearly two decades of correspondence that Murray discovered that the man whose contributions ultimately provided 25% of the quotations for the OED had been working from an asylum. He visited Minor in 1901, wanting to meet him in person and to see the library from which he worked. He also advocated for Minor’s needs and was instrumental in his eventual release from Broadmoor and return to America so that he could spend his last years near family. Minor died in 1920, eight years before the first edition of the dictionary was completed. Murray also did not live to see the work finished; he died in 1915.

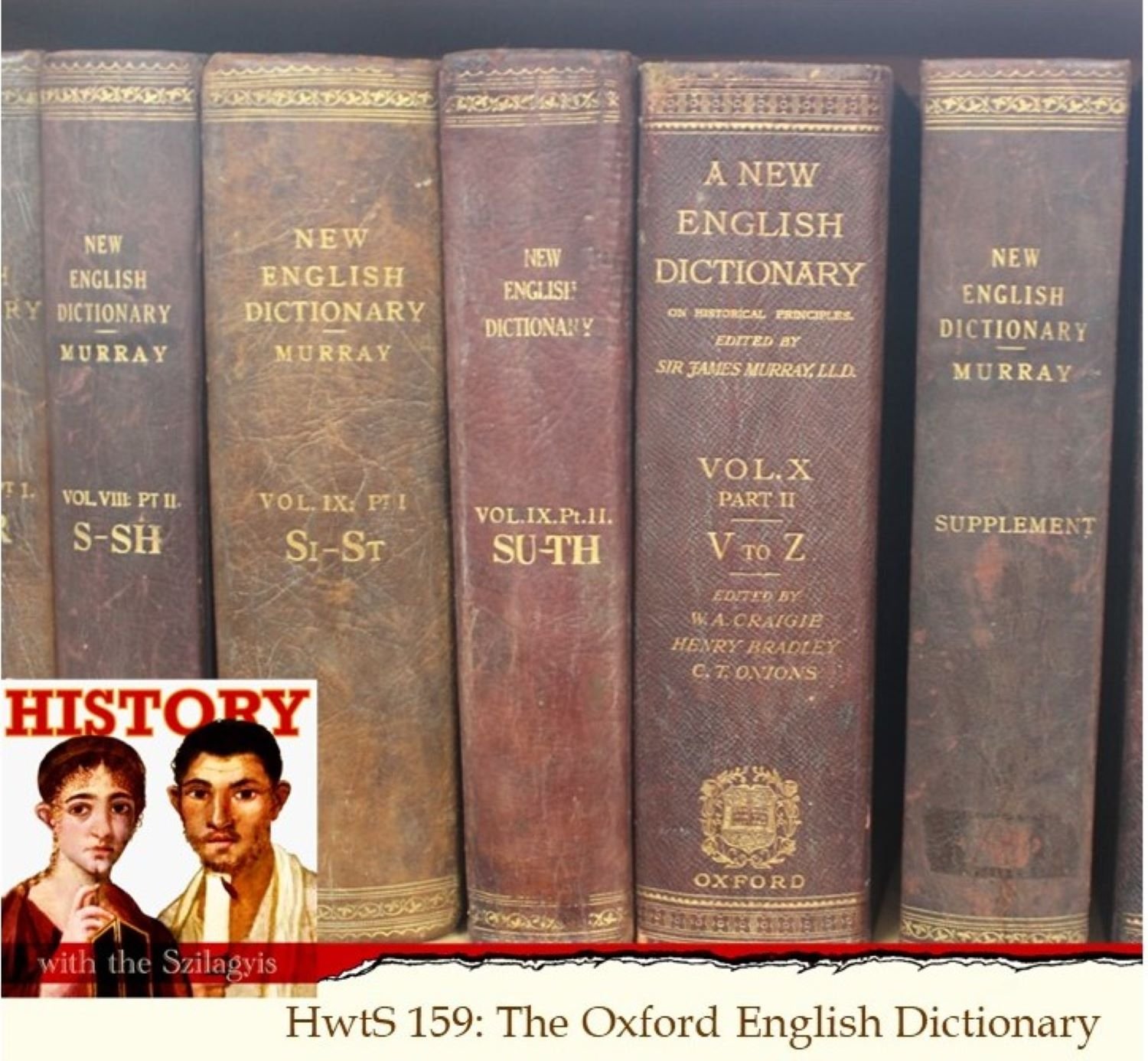

As more and more of the dictionary was completed, the publishers decided to release it in installments. Some had been published intermittently in previous years, but, starting in 1895 a new installment would be released quarterly until the entire project was complete. This continued until the first edition was finalized in 1928, with the exception of some interruptions during the First World War. The complete dictionary, in 12 volumes, was published in full in 1928. A single-volume supplement followed in 1933, along with a reprint of the original twelve. This thirteen-volume set was reprinted in 1961 and 1970.

Work on a second supplement began in 1957, but by the time it was complete, the need to computerize the entire work was evident. This coincided well with the question of how best to provide the supplement: as two additional volumes or integrated into a new edition. The fact that digitizing it required the whole work to be retyped meant that the latter method, which was unquestionably better for the user, could be implemented. This work began in 1983, with 120 typists to transcribe the original work and 55 proofers to check it. Specialized software was produced to create a visual match for the original typography of the first edition, to preserve the original appearance and organization, while also allowing the data to be manipulated separately for any needed changes. The second edition was published in twenty volumes in 1989.

Work on a third edition was begun in 2000, aided by advances in computer software and availability of information (and volunteer readers) via the internet. This edition is expected to be completed in 2037.